Drills on paper, chaos in the field — where is the civil protection culture?

On an early August morning, the aftermath of a drone that fell and exploded exposed more than a few embarrassing details. There were quite a number of security and law-enforcement agencies that responded (albeit only after a conscientious farmer’s call), yet the municipality and residents were essentially left uninformed about what had happened—or it was simply not deemed necessary to tell them.

Why involve the local government?

As long as the local government is not even informed about what happened, we cannot speak of a functioning, broad-based civil protection system. Such a system exists only when there is effective multi-level cooperation. Estonia’s crisis management must not drift into a situation where demands are placed on local governments, yet in a real crisis they are seen—put bluntly—as a superfluous actor. Or worse: they are simply not trusted to be entrusted with important information.

No drone, no problem?

The lack of clear instructions is one of the main obstacles to coping with a crisis—especially when public-safety resources are scarce.

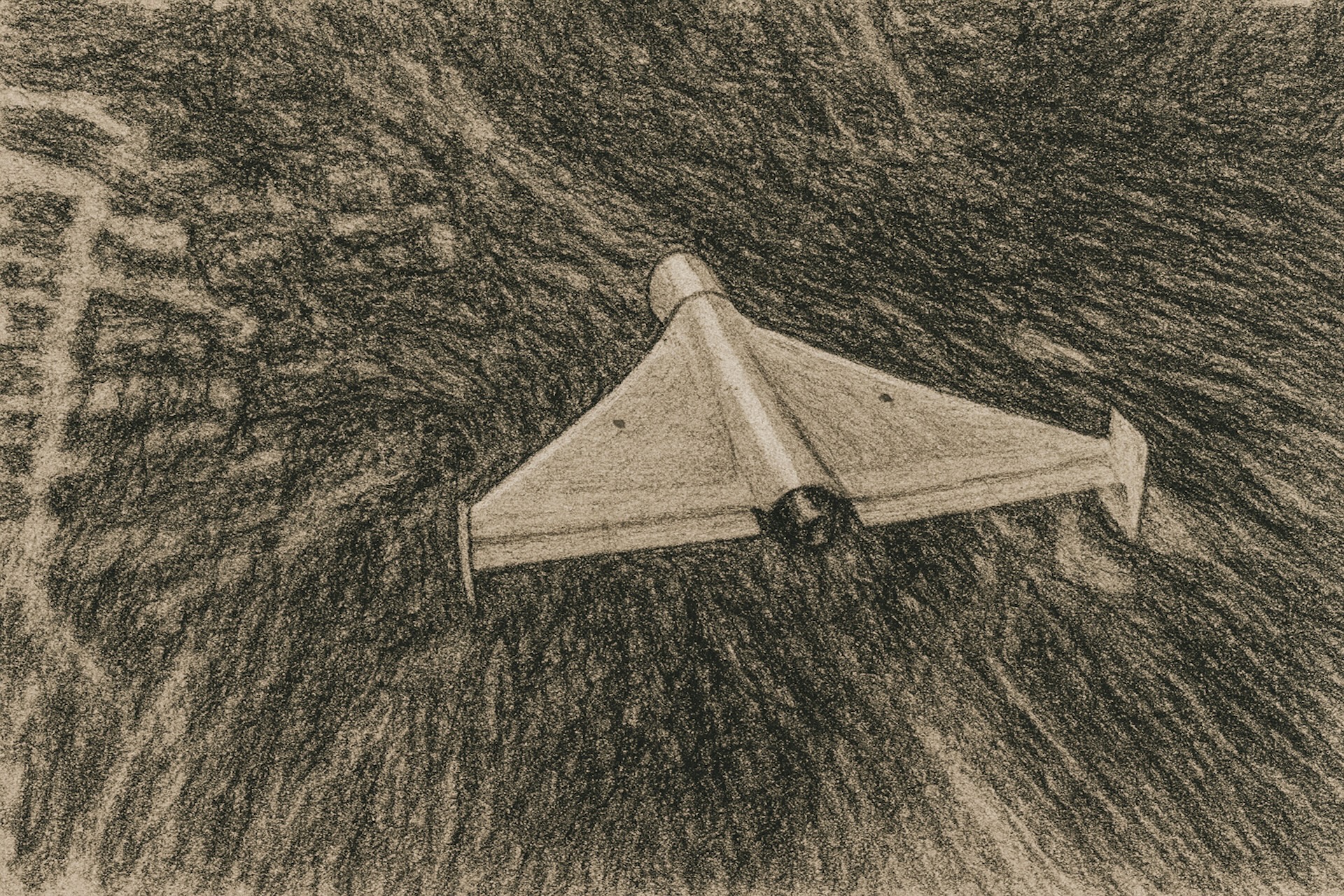

× The op-ed (by Hannes Nagel) was first published on August 29, 2025 on the Estonian Daily web portal. Photo: attack drone in the air (Crisis Research Centre, 2025).

Sources:

1 Viita-Neuhaus, A. 2025. Kohalikku omavalitsust ründedrooni juhtumist ei teavitatud. Postimees, 26.08.2025.

2 Muraveiski, K. 2025. SELGITAJA | Kuidas pääses ohtlik ründedroon üle Eesti piiri ning miks PPA ega kaitsevägi seda ei märganud. Delfi, 26.08.2025.

3 Epner, E. ja Tamme, S. 2025. Saatanlik lõks. Kuidas kujunes sõnum, et Eesti on järgmine. Eesti Ekspress,25.08.2025.

4 Lomp, L.-E. 2025. RESi tuliseim arutelu tuleb palkade üle läbi rääkides. Postimees, 25.08.2025.

Jaga postitust: