The renaissance of Intermarium: a regional vision that could shape Ukraine’s future?

Intermarium was a post First World War geopolitical concept envisioning a union of states stretching from the Baltic Sea to the Black and Aegean Seas, a kind of third power bloc positioned between Germany and Russia. How could reviving this idea benefit Ukraine today?

Intermarium belongs to a long list of geopolitical concepts aimed at fostering unity in Central and Eastern Europe. The original concept envisioned a federation of independent states centred primarily on Poland,8 intended to resist both German and Russian imperialism.9 Since then, efforts have repeatedly been made to revive it in changing contexts, and the events unfolding in Ukraine today may serve as one of the driving impulses for its renewed consideration.

Although Intermarium was destined to fail for purely pragmatic reasons at the time of its creation, the idea has remained, as Polegkyi (2021) notes, an integral part of Polish geopolitics.1 Furthermore, as Kushnir (2021) points out, its weaknesses lay in economic inefficiency and a non-institutionalised framework,1 which was unable to deliver meaningful achievements in either military or defence cooperation.

After Russia’s second invasion of Ukraine, unlike in 2014, there are signs that the former Poland-centric concept may become a reality, albeit under different conditions and on different foundations. Yet it would still be driven by the need to provide a balancing force against imperialism, which this time originates exclusively from the East — an actor determined to avenge the so-called greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century and demanding a return to NATO’s 1997 borders.11 These aims alone constitute an existential threat to the democracies and cultures of Eastern Europe.

According to Nałęcz (2019),12 forming an Intermarium would require at least the free will to create a functioning federal organisation with defensive capabilities, a weakened Russia, and Western approval — conditions1 that never coexisted in the 20th century, unlike today. Paradoxically, the emergence of such a broad, value-based union of states is not threatened by Russian imperialism, but by the potential reliance on a single leader which, as Chakravartti (2022) argues, would (again) most naturally fall to Poland.13 This would repeat the mistakes of the past, because the desire for integration must be shared by all and rooted in the principle of equal treatment — there should be no distinction between small and large states, as the core values and objectives that unite them are universal: the preservation of democracy, freedom, and security.

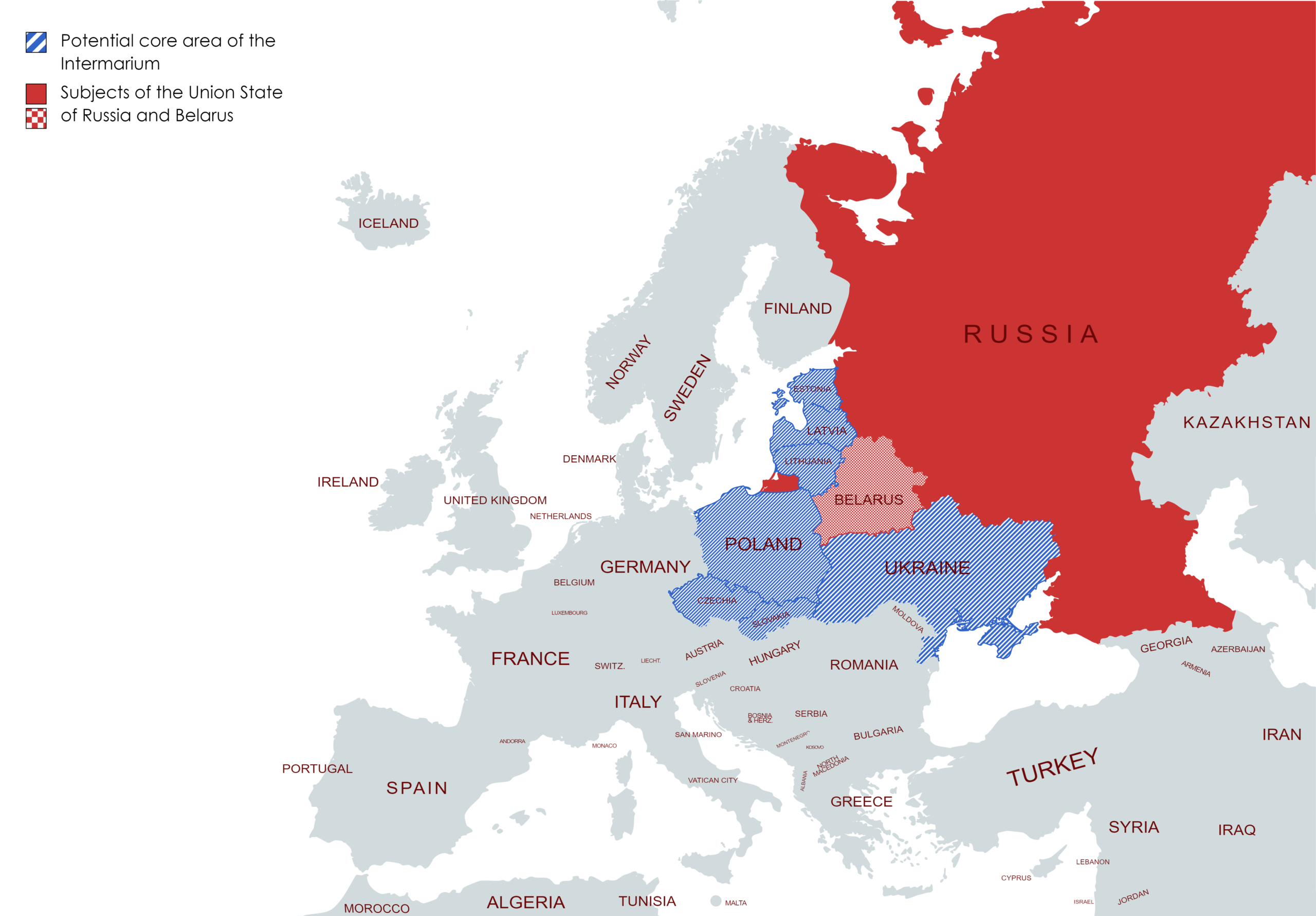

Figure 1. The potential core area of a value-based Intermarium that could accelerate Ukraine’s Euro-Atlantic integration and alleviate the challenges associated with it.14

Despite the fact that Ukraine would benefit the most from such a scenario today, the eastward threat extends across the entire region.14Although there is no guarantee as to whether or how an Intermarium would actually function, or who exactly its members would be, certain aspects can still be highlighted. It would differ significantly from the post–First World War proposal and, in my view, would consist primarily of the Baltic States, Poland, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, and Ukraine (see Figure 1), yet it would have a greater chance of succeeding. Crucially, there are strong historical factors — continuously sustained by Russia’s foreign policy in Eastern Europe — that keep the Intermarium proposal both timely and relevant. Moreover, such an arrangement would complement both a future, larger European Union and NATO through stronger regional ties and alliances.

At the same time, it is also possible that any union under the name Intermarium might function only for a limited period as a springboard toward full integration, where the sharing of accession experiences (and pains) among states that clearly understand the geopolitical dialect of our region could help accelerate and smooth Ukraine’s integration process.

As Estonia’s experience shows, such a phase may be followed by an era in which earlier strong alliances give way to more thematic debates and negotiations shaped by day-to-day political needs — states often vote in groups during EU budget cycles and within EU institutions, depending on the issue and their national positions. True, compromise, the search for common interests, and the formation of voting alliances all play a significant role, but this is the routine reality of everyday politics. It has been done before and will likely be done again. At that point, however, it would be for Ukraine itself to decide which side to align with, join, or support on any given question.

Ukraine’s desire and aspiration to be accepted — and to become part of a broader and genuine European security framework (NATO) and economic framework (the EU), identical to Estonia’s earlier goals — remains in the interest of all parties involved. To put it plainly, without achieving these strategic objectives, Ukraine would remain forever on Europe’s periphery, along with all the dangers and limitations that such a position entails. On a European scale, this would amount to a true geopolitical catastrophe of the 21st century: being so close and yet so far, stuck in the corner of Europe’s waiting room.

Sources:

1 Laruelle, M. & Rivera, E. 2019. Imagined Geographies of Central and Eastern Europe: The Concept of Intermarium, IERES Occasional Papers, 1, p. 3, 8, 13–14.

2 Janusz Cisek (26 September 2002). Kościuszko, we are here!: American pilots of the Kościuszko Squadron in defense of Poland, 1919-1921. McFarland & Company, Inc., p. 47.

3 Spero, J. B. 2004. Bridging the European divide: middle power politics and regional security dilemmas. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., p. 36.

4 Leschnik, H. 2010. Die Außenpolitik der Zweiten polnischen Republik: “Intermarium” und “Drittes Europa” also Konzepte der polnischen Außenpolitik unter Außenminister Józef Beck von 1932 bis 1939, Saarbrücken: Verlag Dr. Müller, p. 32.

5 Dorril, S. 2000. MI6: Inside the Covert World of Her Majesty’s Secret Intelligence Service, New York: Free Press.

6 Aarons, M. & Loftus, J. 1991. Ratlines: How the Vatican’s Nazi Networks Betrayed Western Intelligence to the Soviets, London: William Heinemann.

7 Levy, J. 2006. The Intermarium: Wilson, Madison, & East Central European Federalism, (PhD dissertation), University of Cincinnati.

8 Debo, R. K. 1992. Survival and Consolidation: The Foreign Policy of Soviet Russia, 1918–1992, McGill-Queen’s Press, p. 59.

9 Billington, J. H. 2011. Fire in the Minds of Men, New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, p. 432.

10 Polegkyi, O. 2021. The Intermarium in Ukrainian and Polish Foreign Policy Discourse, Journal of Ukrainian Studies, 8(2), p. 42.

11 Путин, B. B. 2005. Послание Федеральному Собранию Российской Федерации. 25 апреля, Президент России.

12 Nałęcz, D. 2019. The Evolution and Implementation of the Intermarium Strategy in Poland: A Historical Perspective. In Intermarium: The Polish-Ukrainian Linchpin of the Baltic-Black Sea Cooperation, Kushnir, O. (ed.), Cambridge: Scholars Publishing, pp. 15–18

13 Chakravartt, S. 2022. Could the War in Ukraine be a Revival of Polish Geopolitical Ambitions?, Modern Diplomacy, March 16, 2022.

14 Tycner, A. 2020. Intermarium in the 21st Century, Institute of World Politics, December 23, 2020.

Jaga postitust: