Japanese bear crisis

In 2025, Japan is facing one of the most serious human–wildlife conflicts in its recent history. The country is home to two major bear species: the Hokkaido brown bear, a large and powerful northern species, and the Asian black bear, which inhabits the mountainous regions of Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu. Both species typically stay away from populated areas, but this year their behavior has shifted — the surge in attacks, and the growing number of bears appearing in residential areas and even indoors, shows that the usual distance between humans and wildlife is rapidly disappearing.

Bear-related incidents are escalating into a cross-prefectural crisis. In October alone, 88 attacks and seven fatalities were recorded — the bleakest monthly figure in a decade. Between April and October, 13 people were killed and 184 injured by bears across 21 prefectures, with the highest numbers reported in Akita, Iwate, and Fukushima.1

The increase in attacks is the result of several interacting factors. Experts link the situation to both climate change and a growing bear population: storms and shifting weather patterns have damaged the harvest of beech nuts and other forest crops that make up the bears’ main autumn food supply. This year’s acorn and nut yield was particularly poor, leaving mountain-dwelling bears without enough food before hibernation.

Hunger is driving them downhill, where easily accessible food sources — fruit trees, waste, garden produce, and livestock feed — lie at the very edge of villages and towns. As a result, bears are entering settlements more frequently, becoming bolder, and remaining active longer, which increases the risk of encounters and attacks throughout the autumn–winter season.

The impact on local residents is severe

Where villages were once separated from the mountains by a buffer zone of farms and fields, that protective layer has now faded, and bears are moving ever closer to inhabited areas. At the same time, the state has responded forcefully — special units have been dispatched to support local hunters, drones patrol above parks, and researchers have developed a “bear-encounter prediction map” that uses artificial intelligence to forecast risks. Yet tension persists, and everyday routines have changed.

Children are no longer sent to school alone, shops open later, walks are taken only while carrying defensive tools, and tourism has suffered. In communities shaken by bear incidents, fear, exhaustion, and resistance to drastic measures intertwine — some traditional matagi hunters oppose aggressive culling, while some residents demand harsher steps. Amid all this, a shared feeling has taken hold: after years of restrictions and crises, people long for a sense of security, yet now they must live with the knowledge that a bear may be waiting just around the corner.2

Akita Prefecture’s warning to residents on 10 November illustrates the gravity of the situation: in Kazuno City, an Asian black bear attacked a person right outside their home — one of many such incidents that have become more frequent this year. The local government cautions that bears are being spotted far more often than usual even near residential areas, and urges people to make noise while walking outdoors and remain alert to their surroundings to avoid unexpected encounters. Three days earlier, the municipality had issued another notice, reminding residents that bears may not enter hibernation if they continue to find food. For that reason, people are asked to remove late-autumn fruits from trees, collect fallen branches and fruit, and thin out trees if necessary, so that food scents do not keep bears lingering around populated areas.

The bear crisis has also driven innovation in crisis management

ts seriousness is reflected in the involvement of other countries: the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom have recently issued travel advisories regarding bear-related risks in Japan, and the U.S. Embassy in Japan released an official safety alert to American citizens,4 highlighting Hokkaido, Sapporo, and Akita as particularly affected. The recommendations urge people to avoid roads and parks near bear habitats, not travel alone, make noise in nature, carry bear spray, and report encounters directly to local authorities. These guidelines mirror those issued by Japanese municipalities themselves: keep doors and sheds closed, avoid leaving food waste outdoors, clear fruit from trees, protect fields with electric fencing, and improve visibility around homes and farmland.

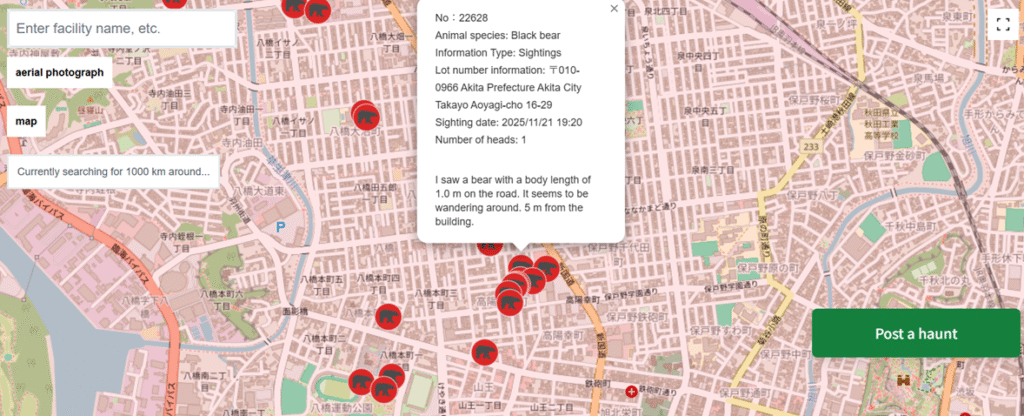

The rapid escalation of the bear crisis has become both a threat and a catalyst for innovation in Japan. To understand the multifaceted risk landscape and support more effective crisis management, researchers from Sophia University’s Applied Data Science Program developed a predictive model that estimates the likelihood of bear encounters in Akita Prefecture.5 The model achieves nearly 64% accuracy and incorporates previous sightings, time and date, land use, population distribution, weather conditions, road networks, elevation, and the availability of beech nuts. Using SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis, a method in Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI), the researchers found that bear appearances are most strongly influenced by patterns of past sightings, land-cover types (such as built-up areas, rice fields, and bamboo forests), the concentration of elderly residents, and terrain elevation. The findings were published on July 22, 2025 in the International Journal of Data Science and Analytics, illustrating how a crisis can accelerate the development of scientific and technological solutions.6

A dedicated crisis map has also been developed for Akita Prefecture to support the management of the bear crisis.8

The bear crisis has also shown how rising demand for practical safety solutions can rapidly generate entirely new innovations. As bears increasingly appear near homes, schools, and camps, a concrete need has emerged for temporary public hiding spaces. Responding to this demand, the company Jacacon, working together with researchers, developed a bear-resistant shelter container — a reinforced, shipping-container-based structure capable of withstanding the force of a brown bear attack and providing people with a safe place to take cover during danger.7 The product is aimed at both private users and municipalities seeking to strengthen protection measures in high-risk areas, and in the Estonian context it is analogous to what is defined as a public hiding place.

Japan’s decision to deploy the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF, 自衛隊) to Akita Prefecture marks a step previously regarded as extreme, prompted by the deepening bear crisis. According to the Ministry of Defense, units are being sent into mountainous areas to set up traps and assist with the removal of dead animals, as local resources are becoming exhausted and the prefectural governor formally requested state support.9 However, the soldiers themselves do not take part in hunting bears — that responsibility remains with local hunters — not because of a lack of capability, but because of constitutional limitations. The JSDF is permitted to use weapons only for self-defense in situations that meet strict criteria related to military attack; they are not allowed to apply force against animals. As a result, soldiers may carry weapons to protect themselves and local residents, but not for bear hunting, and they also lack the training required for such activity. Thus, the state’s intervention in the bear crisis takes shape primarily as logistical and technical support, helping affected regions manage the threat while remaining within the bounds of the constitution.10

The bear crisis also shows the need for resilience hubs

Japan’s 2025 bear crisis is an example of how ecological, demographic, and social factors can erode the balance that once existed in landscapes shared between humans and wildlife. Vegetation damaged by storms and climate change — particularly the poor harvest of beech nuts and acorns — has left bears without food and pushed them toward villages, towns, and farmland. At the same time, rural depopulation and the declining number of hunters have weakened the “buffer” that once existed between people and the mountains, expanding high-risk areas and increasing the number of attacks.

The intrusion of bears into residential neighbourhoods, the disruption of essential services, and the need to involve both the police and the Self-Defense Forces show how a natural hazard can quickly develop into a societal crisis felt across multiple sectors. It is precisely in such situations that the role of resilience centres becomes essential — not merely as places to shelter, but as coordinated support hubs that bring together information, communities, services, and decision-making.

The PIMA project, which focuses on mapping good practices for creating and developing resilience hubs based on Ukraine’s experience and applying them in municipalities in Estonia and Sweden, demonstrates that complex risks cannot be addressed through isolated warning messages or sector-specific measures alone.

What is needed is multi-level cooperation and a unified support structure that helps communities cope both with unexpected military situations and with seemingly “ordinary” environmental hazards that can escalate rapidly. Japan’s experience — where even bear-resistant shelter containers have entered the market as an extension of public services — illustrates how a crisis generates demand for solutions that ensure public safety and the continuity of daily life. Estonia’s own experience with wolf attacks shows similarly that a conflict does not need to reach the scale seen in Japan to require clear, community-aligned leadership. Both the Japanese and Ukrainian examples reinforce the core insight of the PIMA project: cooperation with communities and the establishment of resilience hubs are effective ways to strengthen the capacity needed to help communities withstand both natural and social crises, grounded in knowledge, collaboration, and local needs.

Could the same happen in Estonia?

In Estonia, conflicts between bears and humans have never escalated into a crisis comparable to Japan’s, but signs of tension in human–large carnivore coexistence are present here as well. Estonia’s brown bear population is one of the largest in Europe and has grown steadily over the past decade, leading to more frequent sightings on the edges of settlements and occasional incidents in which hungry or curious bears wander into yards or approach beehives. These cases have not been massive or widely dangerous, as Estonia’s natural food base for bears remains stable and bears are generally wary of humans, but each early-summer incident triggers noticeable public debate.

By comparison, wolves are a much more significant point of tension in Estonia: fluctuations in the wolf population, attacks on livestock, and disputes over hunting quotas have repeatedly drawn public attention and created strong friction between rural residents, conservationists, and authorities. Unlike bears, wolves rarely approach people, but their impact on households is more indirect — through livestock losses, fear, and broader effects on rural life. In both bear and wolf cases, Estonia’s experience shows that the conflict does not necessarily become a direct threat to human life, yet it brings social tension and a need for clear, science-based management that accounts for both community perspectives and nature conservation. This is also a key lesson from Japan’s crisis.

Japan’s solutions to the bear crisis require science-based population management, habitat restoration, and community preparedness, because as long as the mountains fail to provide bears with sufficient food and space, the human–bear conflict will remain a persistent and visible part of daily life in Japan.

Travelling to Japan? Here are 5 tips for staying safe in bear-prone areas::

- avoid walking alone in areas where bears have been seen, and close doors so bears cannot enter buildings;

- keep an eye on your surroundings at all times and avoid places with poor visibility;

- make noise while moving (a bell, radio, phone) to deter bears;

- report every bear sighting to the local municipality and police, and to the community if necessary;

- keep food, feed, and waste containers securely closed or protected with electric fencing.

Images: guidance for residents (Akita Prefecture, 2025). Overview compiled by Hannes Nagel (Crisis Research Centre, 2025).

Sources:

1 [Anon.]., 2025a. October bear attack casualties in Japan hit ten-year high. NHK, 17.11.2025.

2 Hernández, J. C. & Notoya, K. 2025. The Hunt Is On for Bears in Japan After Deadly Attacks. The New York Times, 20.11.2025.

3 [Anon.]., 2025b. クマ出没等に伴う業務の見合わせについて. Japan Post, 5.11.2025.

4 [Anon.]., 2025c. Wildlife Alert: U.S. Embassy Tokyo. U.S. Embassy and Consulates in Japan, 12..11.2025.

5 [Anon.]., 2025d.クマとの遭遇リスクをAIで予測するモデルを開発 [Development of an AI model to predict the risk of bear encounters]. Sophia University, 20.11.2025.

6 Nakamoto, S. & Fukazawa, Y. 2025. Bear warning: predicting encounters using temporal, environmental, and demographic features. International Journal of Data Science and Analytics, 20, pp. 7107–7125.

7 Baseel, C. 2025. Bear attack shelters going on sale in Japan as country experiences record high number of incidents. Japan Today, 17.11.2025.

8 [Anon.]., 2025e. ツキノワグマ等情報マップシステム (クマダス). [Black bear information map system Kumadas].

9 Hernández, J. C. & Kiuko Notoya, K. 2025. Japan to Send Troops to Help Stop Bear Attacks. The New York Times, 29.10.2025.

10 [Anon.]., 2025f. Japan deploys Self-Defense Forces to counter a surge in bear attacks. The Mainichi, 06.11.2025.

Jaga postitust: